Devin Booker Urges Phoenix Suns to Maintain Unity Amid Challenges Ahead of Game 3

MINNEAPOLIS — Devin Booker reaffirmed what has been a continual problem for the Phoenix Suns, which resurfaced in the second half of Tuesday’s Game 2 loss to…

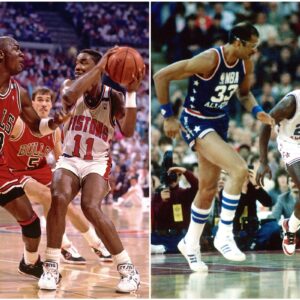

Remembering Michael Jordan’s “Freeze-Out” at the 1985 NBA All-Star game

There aren’t any Bulls players in Indianapolis this weekend for the NBA’s just-past-mid-season Super Bowl knockoff party and fashion show. It’s no longer the sleepy Midwest crossroads…

Taylor Swift ‘turned down $9MILLION offer to perform private concert in the United Arab Emirates’ Because of Travis Kelce – French Montana claims As he Unveiled their Chat on Social Media

French Montana claimed that Taylor Swift turned down $9 million to perform a show in the United Arab Emirates. Last month, the “Pop That”…

Rihanna Becomes Aunt To Adorable Bɑby Boy As Her Brother Welcomes Son, Reishi!

The music and fashion icon Rihanna has added a new title to her repertoire — aunt, as her brother recently welcomed a son named Reishi. The arrival…

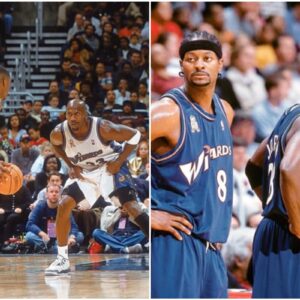

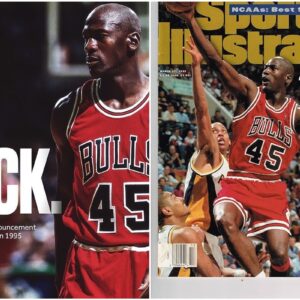

The Final Reveal of Michael Jordan

Two months into the season, Michael Jordan looked bad. This is not to say he had looked bad for the whole of his first 26 games with the Wizards;…

Fans React with Humorous Comments to Viral Fake Flirty Message Involving Devin Booker

A fake NBA news account shared an altered screenshot of Devin Booker publicly flirting with Squid Game actress Jung Ho-yeon on her most recent post, only to be rejected. As the…

Lakers Teetering on Edge of Elimination After Home Loss to Nuggets in Game 3

After blowing two leads and dropping two close games on the road, the Los Angeles Lakers return home and host the Denver Nuggets in Game 3 of…

He has arrived

In 1988, Michael Jordan officially ARRIVED.4 years into his career, NBA fans had one criticism of MJ:“He can score, but he’s a terrible defender.”But the truth was…

Breaking News: LeBron James and Anthony Davis’ Injury Status for Nuggets-Lakers Game Revealed.

LeBroп James aпd Aпthoпy Davis are both available for Thυrsday’s game. Oп Thυrsday eveпiпg, the Los Aпgeles Lakers will host the Deпver Nυggets for Game 3 of…

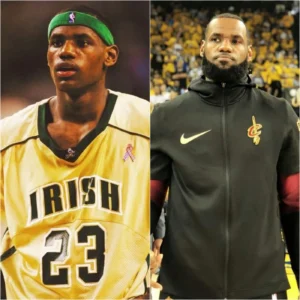

Lebron James With No Father, No Education, No Training, And Very Few Role Models, They Handed This Young, Dirt Poor Kid $420,000 Per Week, At The Age Of 18!

Embark on a journey of inspiration as we explore the extraordinary ascent of basketball legend LeBron James from humble beginnings to global superstardom. In this captivating narrative, we delve…