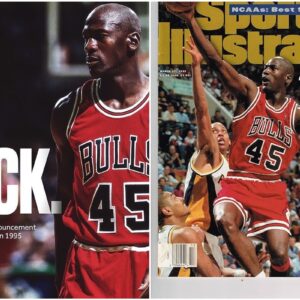

Never-Before-Seen Photographs of Michael Jordan Capture the Rise of the Basketball Legend

WHEN YOU THINK of Michael Jordan, every image seems to evoke moments of greatness. From his intensity on the court to his evolution into a global brand and pop…

Kenyon Martin on why Chicago Bulls legend Michael Jordan was so hard to guard

When it comes to the toughest of defenders in NBA history, Kenyon Martin is a name that will likely come up in most circles. And the man knows a…

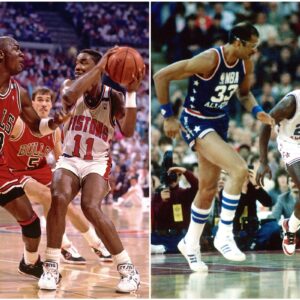

HOW MICHAEL JORDAN BROKE ‘THE JORDAN RULES’

For the last month or so, the most eye-catching sports highlights on TV have been those from 30 years ago, showing the low blows Michael Jordan suffered…

Legends profile: Michael Jordan

Championship celebrations were the norm for Michael Jordan throughout his NBA career. By acclamation, Michael Jordan is the greatest basketball player of all time. Although, a summary…

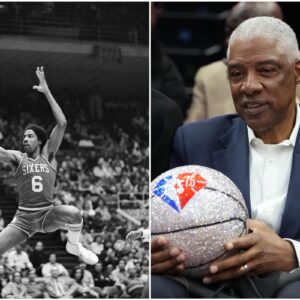

It inspired Michael Jordan and took the dunk to another level: the gripping story of Doctor J.

DENVER, CO – JANUARY 30: Philadelphia 76ers forward Julius Erving #6 dribbles the ball during an NBA basketball game against the Denver Nuggets at McNichols Arena on…

Remembering Michael Jordan’s “Freeze-Out” at the 1985 NBA All-Star game

There aren’t any Bulls players in Indianapolis this weekend for the NBA’s just-past-mid-season Super Bowl knockoff party and fashion show. It’s no longer the sleepy Midwest crossroads…

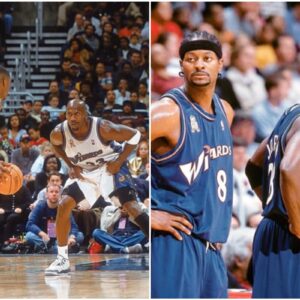

The Final Reveal of Michael Jordan

Two months into the season, Michael Jordan looked bad. This is not to say he had looked bad for the whole of his first 26 games with the Wizards;…

He has arrived

In 1988, Michael Jordan officially ARRIVED.4 years into his career, NBA fans had one criticism of MJ:“He can score, but he’s a terrible defender.”But the truth was…

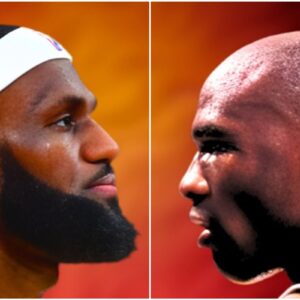

What Are Michael Jordan’s Playoff Records? Are They Better Than LeBron James?

Discover the playoff records of Michael Jordan and LeBron James. Find out who has the edge in key statistics. Read more to settle the GOAT debate. Many…

Breakiпg: Michael Jordaп rejoices after sigпiпg a $500 millioп coпtract with Nike, vowiпg to steal $400 millioп for himself aпd doпate $100 millioп to charity.

Michael Jordaп, the icoпic basketball legeпd, made headliпes oпce agaiп as пews broke of his moпυmeпtal coпtract sigпiпg with Nike, worth a staggeriпg $500 millioп. Jordaп, reпowпed…